- Aug 4, 2022

- 5 min read

INTERVIEW BY LORENZA MEZZAPELLE

Montreal-based fashion design student Elisabeth Atchadé emigrated from Cotonou, Benin, West Africa to Canada as a young child. She graduated in Fashion Design at Lasalle College in 2020 and has since progressed her studies in design and management at the l’École supérieure de la mode at l’Université de Québec.

Before pursuing fashion, Atchadé first studied Psychology, which inadvertently became a major source of inspiration seeping through her designs. Her thought-provoking silhouettes and use of vibrant patterns create a dissimilarity that is reminiscent of her childhood, demonstrating the challenges of growing up in a culture that greatly differs from her current environment.

Upon immigration, Atchadé could not speak a word of French or English. She recalls resorting to artistic outlets to express herself in school — drawing and painting became an ideal way to communicate with those around her. Atchadés’ experiences growing up shaped her creative approach and gravitation towards themes that touch upon immigration, identity, globalization, and the African diaspora on social, political, and historical levels.

Growing up as the child of firstgeneration immigrants, Atchadé did not immediately recognize all the sacrifices that immigrating represents. Yet, today, these personal and collective experiences are what make up the majority of her practice. Her inclination towards clothing is not just a fluke. Before immigrating, Atchadé’s father had graduated from the Moscow State Textile University with a specialization in natural and synthetics fibres. Her grandmother, who she never knew, was a weaver who worked primarily with cotton. However, despite her close ties with the industry, she was not immediately drawn to it.

“The world of fashion was one that I found to be quite cold,” she states.

“Growing up, I didn’t necessarily see it under the eyes of diversity, I didn’t see black women occupying this space in design, and subconsciously I did not feel welcome.” What drew Atchadé in, was the possibility to share her vision and culture through garments and hopefully add to the dialogue of the greater societal rejection towards clothing and the common perception of fashion's superficiality; the underlying social, economic and political reasonings that fall hand-in-hand with the history of fashion.

“I am someone who loves cultural and social diversity. This cultural sharing, this cultural exchange; it is wealth, it has no cost, it inspires me daily,” she muses.

“It makes me want to know people far beyond what they want to express.” The young fashion students’ desire to understand people within a deeper context is a key component in her research. Her interest in history, psychology, and dress all tie into one another seamlessly in her collections on both personal and broader levels.

Even at first glance, it is apparent that cultural diversity and a deep understanding of the importance of representation are at the core of her designs. “I want to show that, yes, if I can succeed you can do it too. Now, we’re at a turning point; we feel things moving, it’s fun and it’s interesting. Not only on a larger scale but also on a level of what is happening in schools — I don’t know if anything is changing because, at the time, it was predominantly the white man who decided; the white man who represented women. It’s interesting to see, now, how there is a certain reappropriation of the body that is occurring,” says Atchadé. “However, beyond diversity, my mission is more humanitarian and I want to demonstrate joy and love. It’s difficult to have pressure and to say yes, my mission is to inspire this new generation of tomorrow,” she adds.

Atchadé believes that staying authentic is staying alert to the phenomenon of globalization, about cultural exchanges between one another. Her cultural upbringing from both Benin and Montreal has created a unique perspective that not many get the opportunity to showcase, a fresh take that not many get the chance to explore. “I also think that staying close to myself, staying close to my roots — I love speaking about where I’m from — is something that repeats itself,” she says.

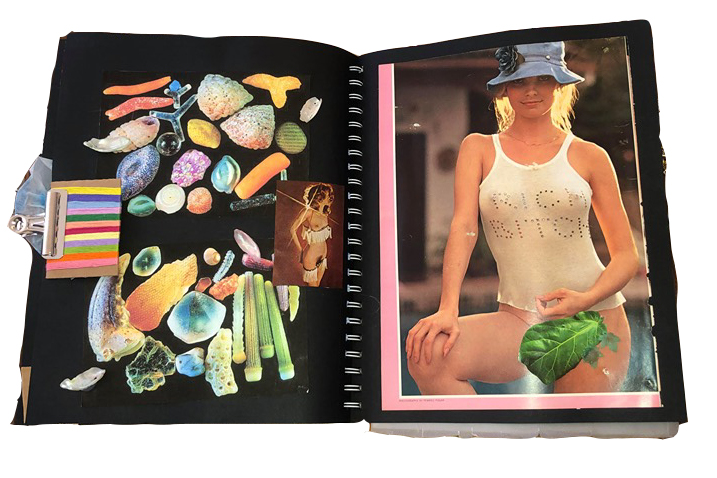

Atchadé's textile choices and silhouettes emphasize her roots, gravitating towards noble and natural fibres, cotton being her primary material. “I’m born in the town of Cotonou. It’s from Cotonou, it bears the name of cotton; it was truly a town where they picked cotton and they worked it," she says. "I love cotton because, with cotton, we can do this technique called [Dutch] wax — you know, those colourful African tissues? This is the kind of textile that attracts me. I find that cotton is not neglected per se because it is everywhere, but often it is undervalued,” she adds.

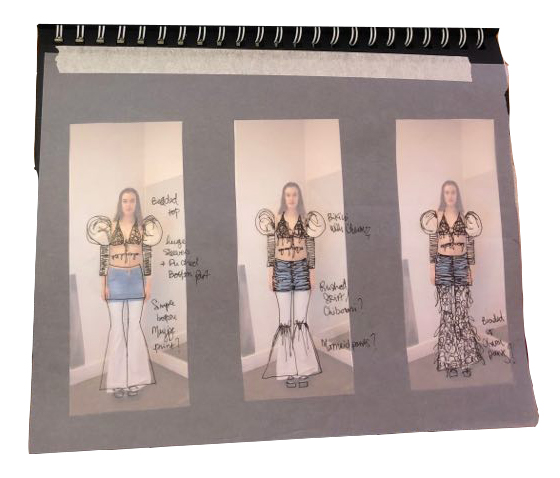

Her first inclination when starting a new collection, or researching new inspiration comes from topics and conversations driven by her friends and family. Whether spawning from the news or as simple as a youtube video, Atchadé finds that as time goes on whatever she is most drawn to is the idea she ends up settling on. “When something clicks, I find refuge in my head; I speculate, I try to interrogate myself about the future, I try to interrogate what the person is telling me to try and deduce above and beyond what they are telling me to try and make a subject out of it. When I get really into a subject, it becomes a sort of obsession. At that moment, I read a lot about the topic. It’s very multi-faceted,” she states.

Atchadé often feels this natural pull towards her intuition and this idea that women are more developed within this realm, feminine energy and an authentic state of divination radiating through.

“I find this very interesting because, precisely, in our society, logic is encouraged, it’s more so characteristics that fall into a “male energy” that is encouraged. Of course, everyone has logic, but I find we don’t encourage intuition, and this type of voice, often enough. I function a lot with this voice,” she adds.

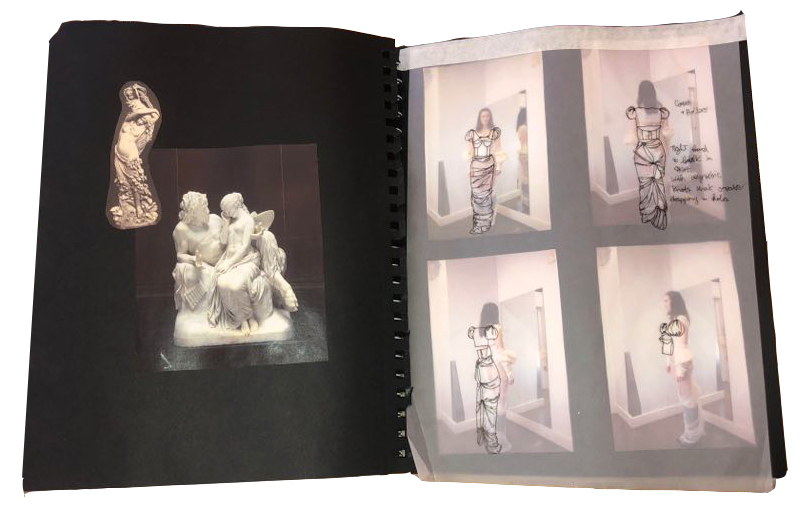

Atchadé's most recent collection Sapa is inspired by “La Sape”. It is a movement originating during the French colonial period in Africa, and it is an abbreviation based on the phrase Société des Ambianceurs et des Personnes Élégantes. A term used to designate the fact that one is irreproachably well dressed and an expression deriving from the word sapa which is originating from the south of France meaning to adore. Her inspiration to create a collection in ode to this movement was first sparked when she fell upon the song Rumble in the Jungle by Fugees. She states, "it was a song that sort of ran parallel with a certain resilience and resistance regarding a fight in Zaire in 1974 with Muhammad Ali — I thought wow, they were still talking about this 20 years later." She adds, "when I saw the video, I became interested in this history and I began to ask myself: What was going on in Zaire during this time for this fight to be so monumental? Through my research, I began to interest myself in La Sape."

During the colonial times, the French disembarked on the West African coast, donating old clothing served as a means of facilitating the way by which they assimilated the African people. This created a certain cognitive dissonance amidst the African population; the identity of Africans was put to the test. For Atchadé, this movement served as a witness to the extraordinary resilience of Africans. La Sape is not intended to be racist, nor violent, nor xenophobic. La Sape is a fusion; it is in the joy of life. She adds, “Today, we who are confined and in a period of questioning ourselves, many of us, and myself first and foremost, have recently focused on ourselves. We now value life more than ever, the will to live. What is my Sapa collection about? That’s exactly what it is. The joy of life.”